Subtotal: 0

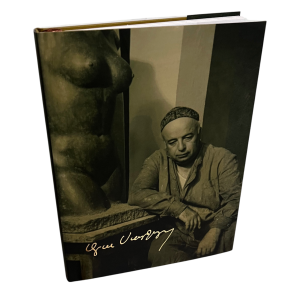

Hakob Kojoyan

Hakob Kojoyan became one of the outstanding graphic-painters of our times, and his art greatly influenced the development of graphic arts in Armenia.

Some of Ilis works arc real innovations done with great skill and mastery.

MARTIROS SARYAN

Hakob Kojoyan was a very delicate, sympathetic man and friend. Being good company he could tell us for hours about art, literature, about the great masters of old times, about his life in Munich, about his future plans and dreams.

He was a man of inexhaustible energy. He could work all day long, for 15-16 hours…

The maul aim of his life was to serve his people and art. He wholly devoted himself to painting, and as a result of this he left for generations his wonderful work’s, which enter Hie Golden Fund of Soviet Art.

ARA SARGSYAN

Life and Artistic Legacy

Hakob Kojoyan was born in 1883 in Akhaltsikhe, where his father worked as a jeweler. His childhood was spent in Vladikavkaz (today’s Ordzhonikidze), where he attended the city gymnasium while also working in his father’s workshop. Under the guidance of his elder brothers, he learned the crafts of goldsmithing, engraving, and chasing. His first known drawing, The Jewellers, dates from 1898.

At the age of sixteen, Kojoyan moved to Moscow to study engraving in the workshop of Prousov. He later continued his education in Munich at the studio of artist Anton Ažbe. His student years in Germany exposed him to the color techniques of the old masters as well as emerging artistic movements. He was particularly drawn to the works of Dürer and the artistic legacies of Holbein and Cranach.

Kojoyan was admitted to the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, graduating in 1907. He then spent two years in Paris before returning to Moscow, where he dedicated himself primarily to easel painting. His creative activity was interrupted by his service during the First World War. Only a few of his early works survive, including Portrait of Dubach and Self-Portrait (1907).

Kojoyan’s mature artistic voice began to emerge after 1918, when he settled in Armenia. That same year, he joined an archaeological expedition to Ani led by Nikolai Marr. The ruins of the medieval Armenian capital—its once-grand palaces, churches, and frescoes—deeply moved him. The watercolor studies he made on-site became the foundation for his painting The Ruins of Ani (1919), in which the fortress walls and palace remnants are depicted in austere brown tones against a blue background. The composition combines simplicity and monumental strength, giving it profound emotional power. More than a documentary record, the work is a philosophical meditation on Armenia’s cultural heritage and historical endurance. Kojoyan revisited this theme repeatedly in later paintings and drawings; one such work, created in 1925, is preserved in the Russian Museum.

In the early 1920s, Kojoyan lived for two years in Tabriz, Iran. His impressions of the region inspired works such as A Street in Tabriz and An Eating-House in Tabriz, as well as large-scale compositions like The Children of Tabriz, Persian Bazaar, Persian Woman, and The Tabriz Dogs.

In 1922, invited by the Soviet Armenian government, Kojoyan returned to Yerevan and became actively involved in shaping the cultural life of the young republic. His art during the 1920s was marked by remarkable diversity—he worked in easel painting, graphics, and metal chasing, while also illustrating early Soviet Armenian books and periodicals. Alongside landscapes, he created works on historical and revolutionary themes.

Among his most accomplished works of the decade is the graphic composition David of Sassoun, inspired by the Armenian national epic. The central figure, David, brandishes the sword Tur-Ketsaki, surrounded by scenes from the poem—his childhood, the punishment of Kozbadi, and the death of King Melik of Msra. The work’s internal structure recalls a miniature: fortress walls, monastery outlines, heroic figures, and ornate motifs rendered in delicate pastel tones. The harmony between composition and line lends the piece artistic unity.

Equally refined is The Women of Akhaltsikha, which portrays women in traditional costumes against a richly patterned background of floral and geometric designs. Every detail of the garments and ornaments is executed with precision and taste, each rosette uniquely drawn.

Other notable works of the period include An Armenian Town-Crier, The Sleeping Persian Woman, and Armenian Stylization, characterized by fairy-tale motifs, ornamental richness, and elegant linear rhythm.

In 1925, Kojoyan illustrated Stepan Zoryan’s fairy tale Hazaran Blbul (The Nightingale of a Thousand Voices). Captivated by its lyricism, wisdom, and fantasy, he vividly conveyed its poetic spirit in his drawings.

After returning to Armenia, landscape painting became one of his dominant genres. Works such as Lonely Oak: Kirovakan, The Mountains of Kirovakan, and Aparan Village feature soft hues of brown, gray, violet, and green, rendered with expressive brushwork. His Geghard Monastery landscapes, executed in tempera, show a more restrained palette that highlights the contours of mountains, caves, and ancient walls. One of his most poetic canvases, Autumn in Yerevan, captures a solitary tree, fallen leaves, and a stone fence with lyrical delicacy.

Kojoyan’s contribution to book illustration occupies a central place in Armenian art history. His work in the 1930s laid the foundation for the national school of book design. Deeply attuned to the literary essence of each work, he combined imagination with expressive visual language. His illustrations for The Book of the Road by Yeghishe Charents, Poems and Legends by Maxim Gorky, The Daredevils of Sassoun, Poems by Avetik Isahakyan, and stories by Aksel Bakunts are among the finest examples.

Collaborating closely with Charents, Kojoyan designed The Book of the Road, interpreting the poet’s reflections on the evolution of human civilization through visual rhythm and symbolic imagery. “I was impressed by the depth of his thoughts and his skill in leading readers to relive the events he described,” Kojoyan later wrote of Charents.

In 1934, he illustrated the first Armenian edition of Gorky’s Poems and Legends. His use of spatial layering and compositional depth drew praise from Gorky himself when the works were exhibited in Moscow during the First Congress of Soviet Writers. These illustrations are now housed in Gorky’s Memorial Museum.

Rooted in the traditions of Armenian art, Kojoyan mastered both pictorial and graphic forms. He was a connoisseur of medieval Armenian ornamentation, khachkar carvings, manuscript miniatures, and decorative motifs. Rather than merely imitating these sources, he transformed them into his own expressive visual language. In his title pages and headpieces for David of Sassoun and Anthology of Armenian Verse, one senses the spirit of ancient Armenian manuscripts, while his Aghvesagirk illustrations reinterpret medieval animal-shaped initials with modern artistry.

Kojoyan approached each book as an integrated whole, believing that its structure and visual form should arise from its content. This philosophy reached its peak in his illustrations for Anthology of Songs and Poems by Sayat-Nova in the 1940s, where the lines, colors, and composition harmonize seamlessly with the poet’s lyrical imagery. Other important works from this decade include illustrations for Selected Poems by A. Isahakyan and Ara the Beautiful by Nairi Zarian.

Across three decades, Kojoyan illustrated an impressive range of works—poems, folk tales, and historical stories—imbued with vitality and artistic refinement. Reflecting on his craft, he once said:

“I have worked extensively on the problems of graphics, focusing above all on quality. Illustrations must convey the true atmosphere of the book and portray its characters vividly and truthfully. My favorite works are those I created for Gorky, Charents, Zarian, and Sayat-Nova.”

A recurring symbol in Kojoyan’s art was the phoenix—a bird reborn from its own ashes—embodying for him the immortality of art.

In 1956, he illustrated Hovhannes Tumanyan’s Parvana, once again expressing the theme of love as a symbol of life and human beauty. Both artist and poet shared a deep reverence for Armenian folklore, music, and tradition as the living roots of creativity.

Kojoyan’s early training in metalwork also fostered his lifelong interest in applied arts. In the 1920s he created designs for silverware, and in the 1950s he turned to ceramics. His sketches for jugs, cups, and plates often feature ornamental motifs, vegetal patterns, and mythic birds of love. His Sayat-Nova Plate depicts the bard surrounded by intricate filigree, while another design portrays a stylized Armenian maiden—both rooted in national folk aesthetics.

Kojoyan remained active until the end of his life. He passed away in the spring of 1959. His works are held today in the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, the Museum of Oriental Art in Moscow, the Museum of Russian Art in Kyiv, and the National Gallery of Armenia. His art gained international recognition as early as the 1930s, when his graphic works were exhibited in London, Philadelphia, and Danzig.

In 1973, the Hakob Kojoyan House-Museum opened in Yerevan, exhibiting his paintings, drawings, and one of his last works, David of Sassoun (1958). On the easel in his preserved studio rests his unfinished canvas, The Ruins of Ani—a testament to a lifetime devoted to the beauty and endurance of Armenian art.